Validation and interpretation#

Validate input#

It is always a good practice to spend some time to evaluate the quality and representativeness of input data before diving into the analytics. Input data can contain errors and artefacts; sometimes they are large and evident, sometimes they are small and hard to catch - but that doesn’t mean they don’t have an impact over the quality of results!

Hazard#

Correct values interpretation and outliers#

Check layer projection sysyem (CRS) and resolution

The CRS should be the same for all layers involved in the analysis, e.g.

WGS 84 - EPSG: 4326

Check unit of measure (hazard metadata)

Is the unit of measure the same as expected by the vulnerability model? E.g. flood depth could be expressed in centimeters, meters, or by classes

Check values distribution (histogram)

Is the range rapresented compatible with the unit of measure? Are there outliers?

Set a proper cut for outliers

Set up appropriate classification and symbology (legend)

This could be quantitative o categorical depending on the data

Geographic correlation#

This is easier to check for hazards with strong dependency to the geomorphology, such as floods and landslides. An inspection of hazard layers against a reliable basemap (e.g. ESRI or Google) can help to spot inconsistencies between the representation of hazard distribution and its expected behaviour (rule of thumb) in relation to the basemap.

Some examples:

River flood extent occurring too far from its catchment; depth values not matching with the elevation from digital terrain model.

High landslide hazard on flat terrain.

Coastal floods spreading inland for kilometers on coastal plains.

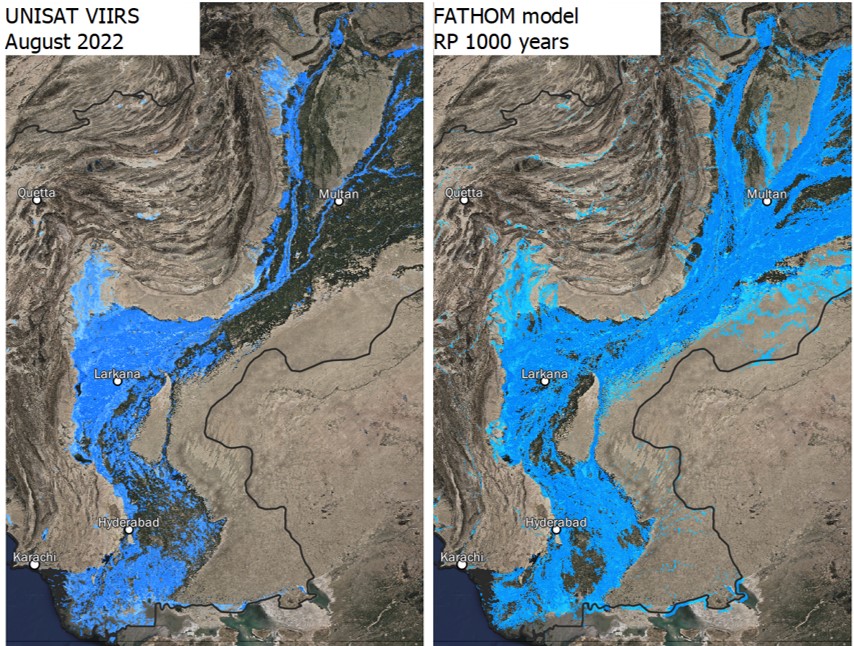

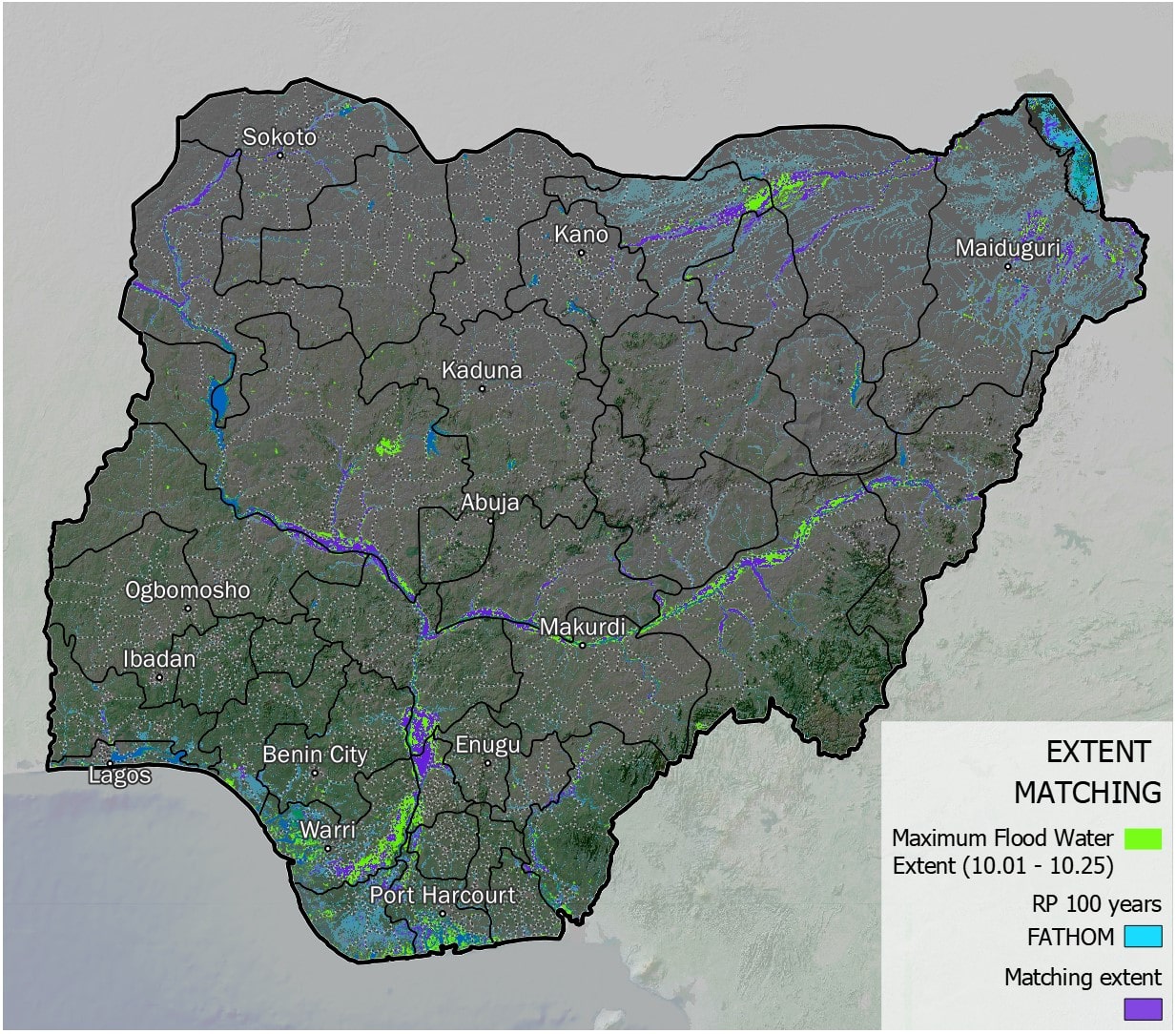

Comparison against empirical datasets#

Probabilistic scenarios of hazard data can be compared with observed disaster events to corroborate the analysis, although this is often a difficult task due to lack of granular spatial data representing the events. Some hazards are better covered by observations than others - see the disaster records.

Fig. 36 Example of flood model extent validation between observed events (UNOSAT, Pakistan 2022) and probabilistic model (Fathom RP 1,000 years).#

Fig. 37 Example of flood model extent validation between observed events (UNOSAT, Nigeria 2022) and probabilistic model (Fathom RP 100 years).#

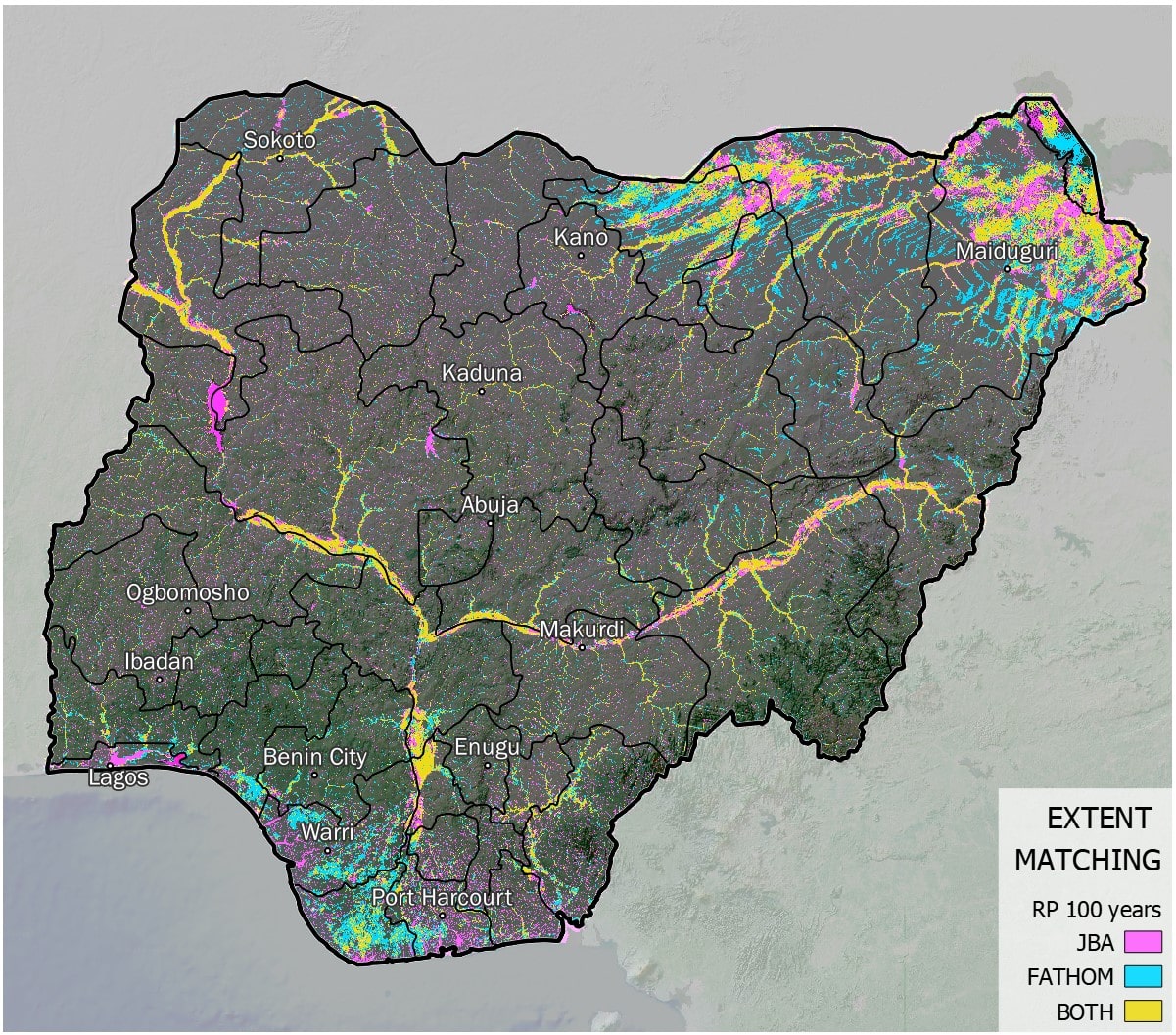

Cross-comparison between alternative datasets#

Run a spatial and numerical comparison between models to estimate their similarity.

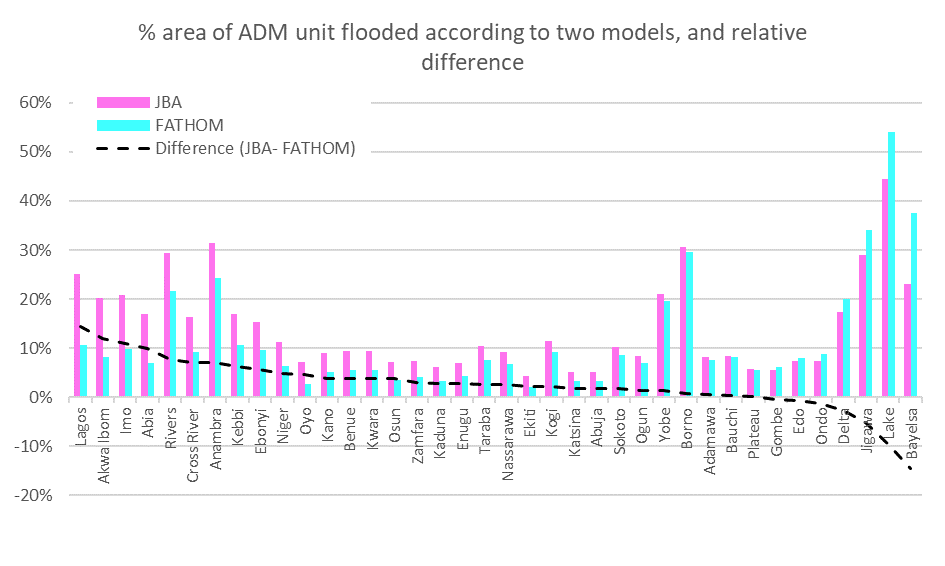

Fig. 38 Example of map showing cross-comparison between two different models representing probabilistic flood hazard extent over Nigeria (RP 100 years).#

Fig. 39 Example of chart showing cross-comparison between two different models representing probabilistic flood hazard extent over Nigeria (RP 100 years): share of affected sub-national area according to each model, and difference between the two models.#

Exposure#

Correct values interpretation and outliers#

Check layer projection sysyem (CRS) and resolution

The CRS should be the same for all layers involved in the analysis, e.g.

WGS 84 - EPSG: 3857

Check the exposure category and unit of measure (exposure metadata)

Is the unit of measure the same as expected by the vulnerability model? E.g. population could be expressed as count, density, percentage. Land cover values could be binary or categorical

Check values distribution (histogram)

Is the range rapresented compatible with the unit of measure? Are there outliers?

Set a proper cut for outliers

Set up appropriate classification and symbology (legend)

This could be quantitative o categorical depending on the data

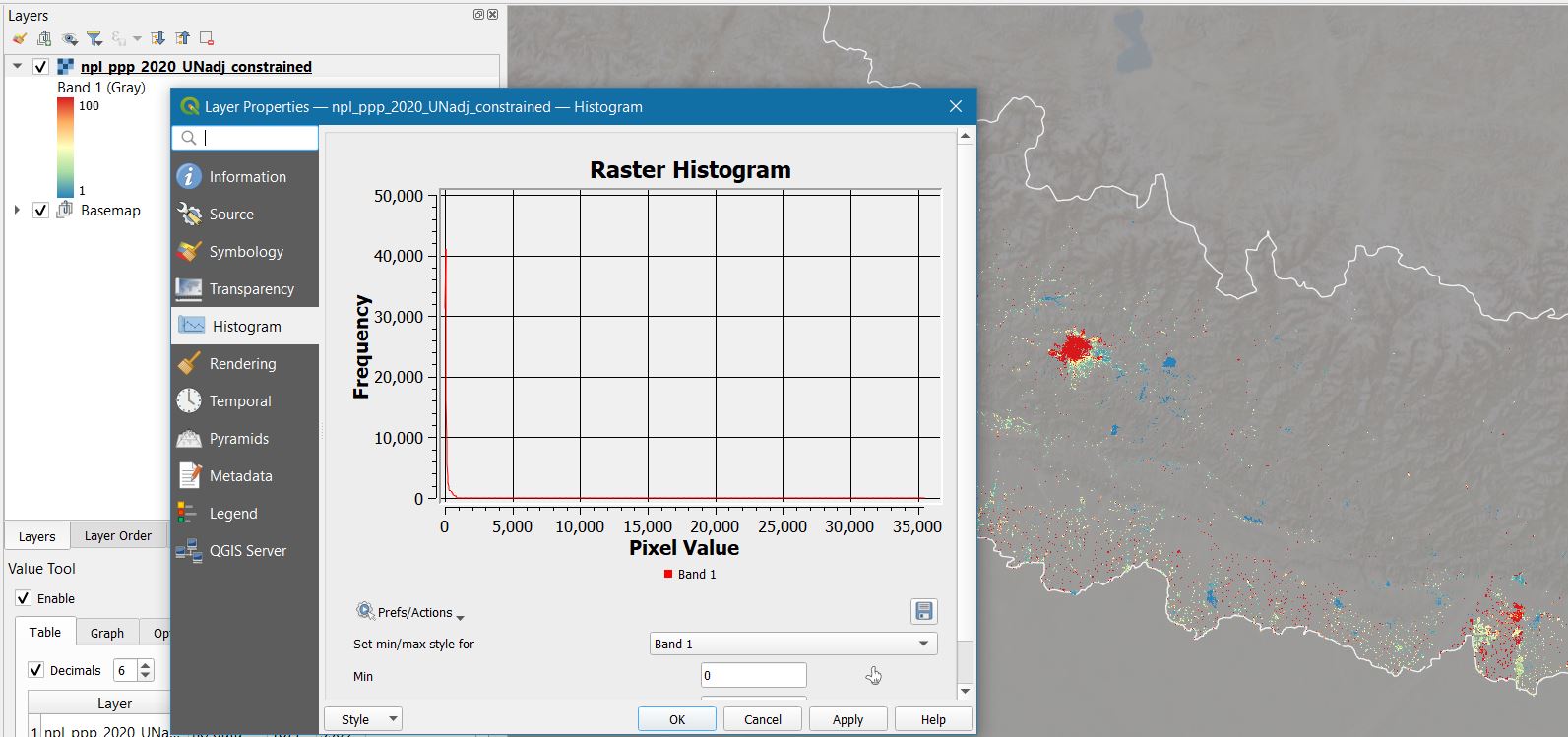

Fig. 40 In this example, we are examining the WorldPop 2020 population layer for Nepal (UN-adjusted, constrained to built-up). The resolution is 100 x 100 meters = 1 Ha; initially, we set the max legend to spectral (blue-yellow-red) and the threshold to 100, to better spot high-density areas (red). Then we take a look at the histogram, and we notice that the population values go up to 35,000, equal to 3.5 per square meter. That seems reasonable only for very-high density areas with tall buildings (meaning that the people can distribute vertically over the same cell). While those value seems unrealistic elsewhere.#

Comparison against basemap#

Identify artifacts in exposure data by sample inspection; if the errors are limited and a better source of truth is available for comparison, fix them manually; else, account for them in the results interpretation and uncertainty.

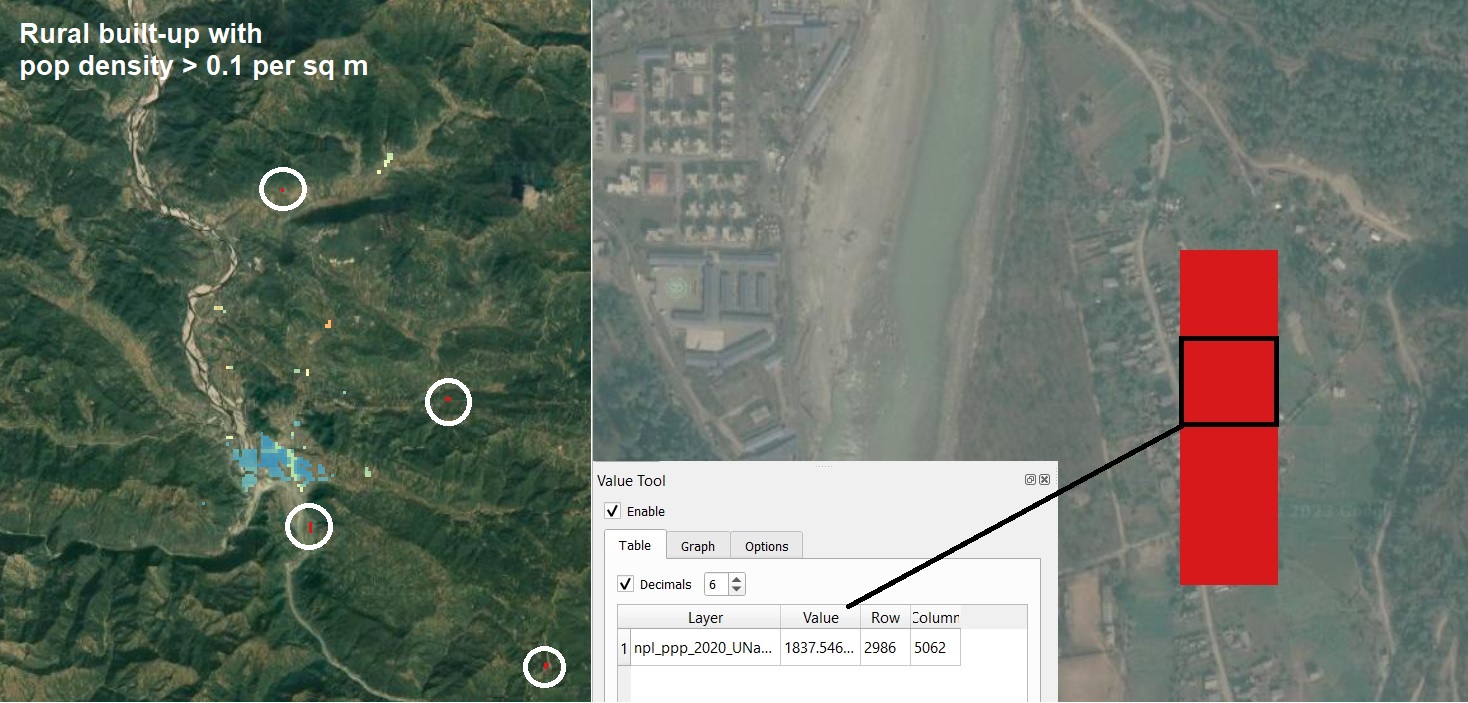

Fig. 41 Following on the previous example over Nepal; let’s change the legend max to 1,000 and take a closer look to high-density pixel (> 0.1 people per square meter). Let’s go sampling now, select any high density area located outside large city areas. Then zoom in, and compare the value of the pixel with the size and type of built-up according to recent google basemap. In the higlighted case, it seems very unlikely that >1,800 people live in that hectar of rural built-up. We also notice how other built-up area are not captured by the data; we can conclude that the model erroneously project population from the whole census area into a small portion of the real built-up. This would not have an important effect on more uniformely-distributed hazards (e.g. heat, air pollution), but it can introduce huge errors in risk calculations for localised hazards such as floods and landslides.#

Cross-comparison between alternative models#

Run a spatial and numerical comparison between models to estimate their similarity.

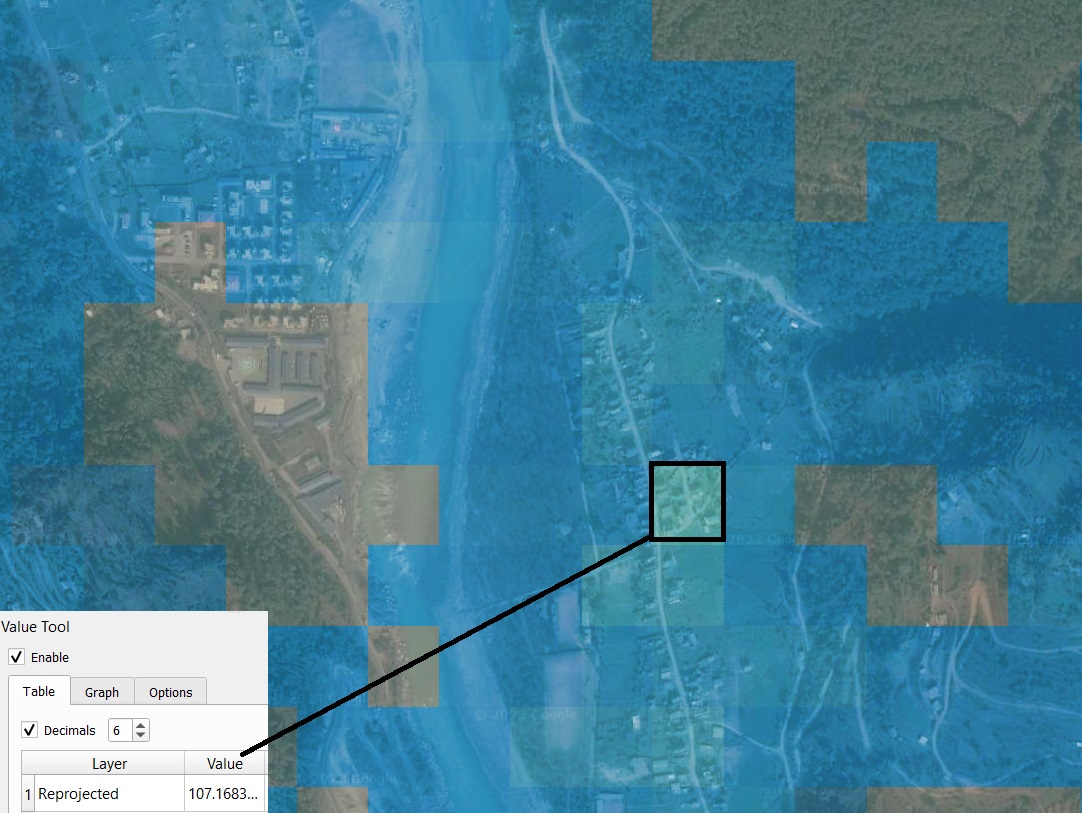

Fig. 42 Following on the previous example over Nepal; we now load the GHS-pop 2020 layer and attribute the same projection and legend used for the WorldPop layer (and set the rendering to “overlay” for better visualization). We notice that the values are much more realistic in this case; on the counterside, low population values are distributed also in areas where no settlement is found. This can also introduce error in risk models, depending on the hazard. For this country, neither of the two population datasets examined is flawless and can’t be manually fixed. This must be accounted in the interpretation of results and discussion of uncertainty.#

Output interpretation#

The analytical model produces numbers; then is to the ability of the risk analyst to interpret them correctly, spot errors, and build a narrative to make the results digestable for a non-expert audience.

Validation against empirical disaster data#

First, check that results make sense in terms of metrics and units of measures.

Relative impacts over 100% are always a good indicator that something went wrong.

Does the calculated distribution of risk reflect the historical distribution of disaster events as recorded by catalogues (e.g. EM-DAT) and agencies (e.g. reliefweb)?

If not, can you explain the reason?

Uncertainty#

In the development of risk models, many different data sets are used as input components. The level of uncertainty is directly linked to the quality of the input data. In addition, there is also random uncertainty that cannot be reduced. On many occasions during model development, expert judgment and proxies are used in the absence of historical data, and the results are very sensitive to most of these assumptions and variations in input data. As such, outputs of these models should be considered indicators of the order of magnitude of the risks, not as exact values. Better data quality and advances in science and modelling methodologies reduce the level of uncertainty, but it is crucial to interpret the results of any risk assessment against the backdrop of unavoidable uncertainty.

A risk model can produce a very precise result—it may show, for example, that a 1-in-100-year flood will affect 388,123 people—but in reality the accuracy of the model and input data may provide only an order of magnitude estimate. Similarly, sharply delineated flood zones on a hazard map do not adequately reflect the uncertainty associated with the estimate and could lead to decisions such as locating critical facilities just outside the flood line, where the actual risk is the same as if the facility was located inside the flood zone.

We should not be apprehensive of using information that is uncertain so long as any decisions and actions based upon the information are made with a full understanding of the associated uncertainty and its implications. It should be remembered that uncertainty will usually promote an analytical debate that should lead to robust decisions, which is a positive manifestation of uncertainty. Credible scientific results should always be presented together with their associated uncertainty.