Geophysical hazards#

Natural hazards that originate from processes occurring within the Earth’s interior or its immediate surroundings. These processes can include seismic activity (earthquakes), volcanic eruptions, and tsunamis. Geophysical hazards often have a sudden onset, meaning they can occur with little to no warning for preparedness or evacuation and cause widespread impacts, affecting large areas far from the source of the hazard. Geophysical hazards are not influenced by climatic conditions, but on the other side they can affect climate.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) offers a global Natural Hazard Viewer monitoring geophisical hazards (Earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic activity).

Earthquake#

Earthquakes can strike any location at any time, but history shows they occur in the same general patterns year after year, principally in three large zones of the earth:

The world’s greatest earthquake belt, the circum-Pacific seismic belt (“Ring of Fire”), is found along the rim of the Pacific Ocean, where about 81% of global earthquakes occur. Earthquakes in these subduction zones are caused by slip between plates and rupture within plates. Earthquakes in the curcum-Pacific seismic belt include the M9.5 Bio-Bio earthquake in Chile (1960) and the M9.2 Great Alaska Earthquake (1964).

The Alpide earthquake belt extends from Java to Sumatra through the Himalayas, the Mediterranean, and out into the Atlantic. This belt accounts for about 17% of the world’s largest earthquakes, including some of the most destructive, such as the 2005 M7.6 shock in Pakistan that killed over 80,000 and the 2004 M9.1 Indonesia earthquake, which generated a tsunami that killed over 230,000 people.

The third prominent belt follows the mid-Atlantic Ridge running deep underwater and far from human development, with the exception of Iceland, which sits over the ridge.

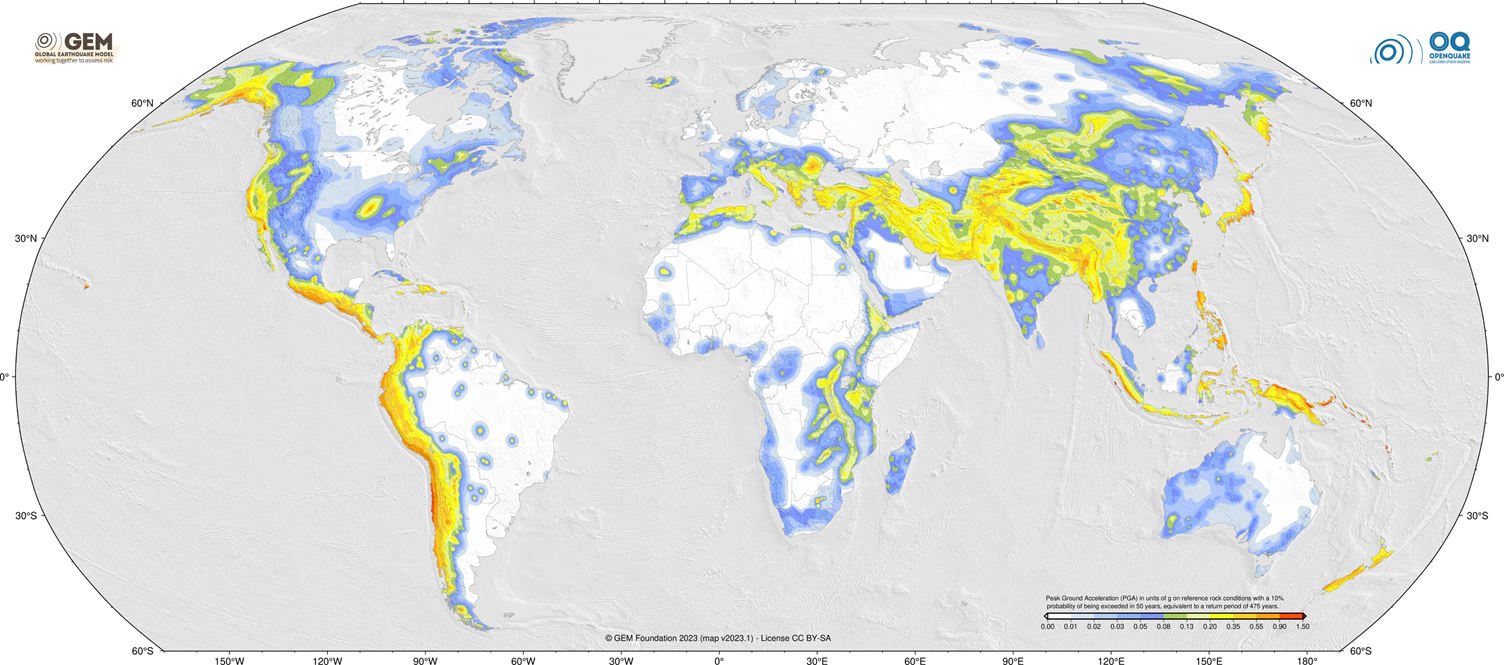

Open global earthquake dataset representing seismic hazard intensity as peak ground acceleration have been produced for the Global Assessment Report (GAR).

The Global Earthquake Model (GEM) offers a range of datasets related to seismic hazards, including an interactive global seismic hazard map viewer, global historical earthquake catalogue, active faults, vulnerability functions, exposure data and country risk profiles. Some of the datasets have commercial licensing, while most of them are open for non-commercial use (CC-BY-SA).

Fig. 11 Global Earthquake Model 2023 - Peak Ground Acceleration (PGA) with a 10% probability of being exceeded in 50 years, computed for reference rock conditions (shear wave velocity, Vs30, of 760-800 m/s).#

See also

Open Python script to generate earthquake maps.

Tsunami#

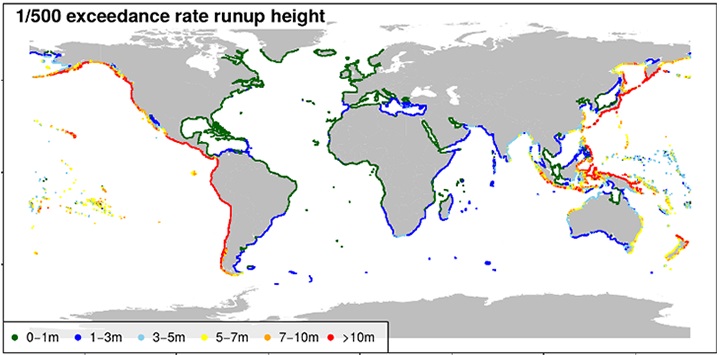

The Global Tsunami Model (GTM) has been created by a group of tsunami experts around the world to provide coordinate action for tsunami hazard and risk assessment. It offers a global probabilistic tsunami hazard assessment from earthquake sources Davies et al. 2018.

Fig. 12 Global Tsunami Model - run-up height, RP 500 years.#

The NOAA offers global long-term historical database of tsunami runup documenting the impacts of tsunami events worldwide. This database provides detailed information on tsunami runup occurrences—instances where tsunami waves inundate coastal areas. Each entry in the database includes critical data such as: - Geographic Coordinates: Precise latitude and longitude of observation points. - Event Details: Date, time, and location of the tsunami event. - Runup Measurements: Maximum water heights recorded, which indicate the extent of inland penetration by tsunami waves. NGDC - Impact Assessments: Information on casualties, property damage, and other effects associated with each runup event.

Volcanic activity#

Volcanic eruptions occur most frequently at plate boundaries, but some volcanoes (e.g. Hawaiian Islands) occur in the interior of plates, at areas called hot spots. The greatest number of the Earth’s volcanoes are hidden from view, occurring on the ocean floor along spreading ridges. Volcanic hazards can include various phenomena, such as lava flows, pyroclastic flows, ashfall, volcanic gases, lahars (mudflows), and volcanic landslides. In disaster risk management, understanding the types of volcanoes and volcanic eruptions is crucial for assessing the associated hazard and risk levels.

Shield Volcanoes: broad, gently sloping sides formed by low-viscosity lava flows. Eruptions are typically non-explosive, with the lava flowing steadily from fissure vents or central craters. The primary hazard is the lava flow, which can move relatively slowly, allowing for evacuation and minimal loss of life. Risk levels can vary depending on population density near the volcano and the speed of lava flow.

Stratovolcanoes (Composite Volcanoes): steep-sided cones composed of alternating layers of lava, ash, and volcanic debris. Eruptions can range from explosive to effusive, producing pyroclastic flows, ash clouds, and lava flows. The hazards associated with stratovolcanoes are diverse and include pyroclastic flows, lahars, ashfall, and volcanic gases. Risk levels can be high, particularly if densely populated areas are located near the volcano.

Cinder Cones: small, conical volcanoes built from ejected lava fragments (cinders) that accumulate around the vent. Eruptions are typically short-lived and explosive, characterized by gas-rich explosions that propel volcanic bombs and ash into the air. Hazard levels are generally moderate, with risks mainly related to ashfall, ballistic projectiles, and potential lava flows.

Calderas: large, basin-shaped depressions that form after the emptying of a magma chamber during a volcanic eruption. Eruptions associated with calderas can vary in explosivity, producing pyroclastic flows, ash clouds, and lava flows. Hazard levels can be extremely high, especially during large-scale eruptions, which may result in widespread devastation and long-term effects on climate and air quality.

The Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program (GVP) offers a catalogue of current and past activity for all volcanoes on the planet active during the last 10,000 years. The Significant Volcanic Eruptions Database is a global listing of over 600 eruptions from 4,360 BC to the present. A significant eruption is classified as one that meets at least one of the following criteria:

caused fatalities

caused moderate damage (approximately $1 million or more)

Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) of 6 or greater

generated a tsunami, or was associated with a significant earthquake.

The database layer provides information on the latitude, longitude, elevation, type of volcano, last known eruption, VEI index, and socio-economic data such as the total number of casualties, injuries, houses destroyed, and houses damaged, and $ dollage damage estimates. References, political geography, and additional comments are also provided for each eruption. If the eruption was associated with a tsunami or significant earthquake, it is flagged and linked to the related database. An additional source is the British Geological Survey LaMEVE (Large Magnitude Explosive Volcanic Eruptions) database.

See also

Open Python script to generate interactive volcanoes map.