The Philosophy of Mapping#

The practice of mapping the world is not simply a technical endeavor — it is a philosophical act, an attempt to render the vastness of reality into a symbolic, intelligible form. The roots of this practice trace back to the ancient Hellenic world, where geography, astronomy, and philosophy intertwined in early efforts to understand and represent the Earth.

The Pioneers of Ancient Cartography#

Eratosthenes of Cyrene: The Father of Geography#

One of the earliest systematic attempts at mapping the known world came from the Greek scholar Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 276–194 BCE), a polymath who served as the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandria. He is often credited as the “father of geography.” His most notable contribution was the calculation of the Earth’s circumference with remarkable accuracy for his time, using simple geometry and observations of shadows in Syene and Alexandria during the summer solstice. Based on this, Eratosthenes devised one of the first known gridded maps of the inhabited world, laying out meridians and parallels in an early conceptualization of geographic coordinates.

Fig. 49 Reconstruction of Eratosthenes’ map of the known world#

Eratosthenes’ map was an extraordinary achievement: not just in terms of its scale and detail, but in how it was underpinned by a clear theoretical understanding of the Earth as a sphere and of geography as a branch of mathematical science. This highlights how Eratosthenes’ work went beyond empirical observation into the realm of abstract reasoning—a hallmark of Greek philosophical inquiry.

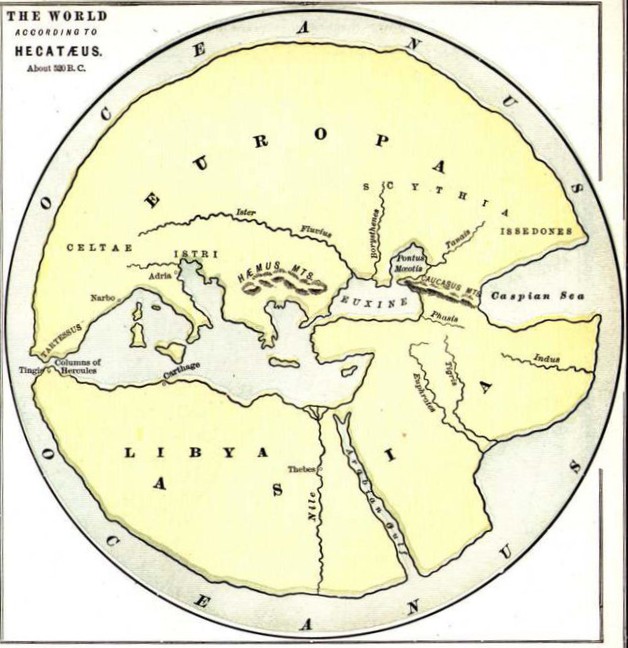

Anaximander of Miletus: The First World Map#

Prior to Eratosthenes, Anaximander of Miletus (c. 610–546 BCE) is often cited as the first to draw a map of the world, though none of his works survive. According to later sources, his map represented the known world as a circular disk floating in space, surrounded by ocean. This representation was not just geographical — it reflected a metaphysical cosmology. The Earth was conceived as a central, balanced entity, suggesting an underlying harmony and order to the universe, a theme common in pre-Socratic thought.

Fig. 50 Reconstruction of Anaximander’s world map#

Ptolemy: Systematizing Cartographic Principles#

Later figures like Ptolemy (c. 100–170 CE) in the Roman period built on these foundations. His Geographia systematized cartographic principles and introduced projections to transform the spherical Earth onto a flat surface — a challenge that lies at the heart of the philosophy of mapping: how to translate reality from one dimension to another without distortion.

The Philosophical Dimensions of Mapping#

In these early efforts, we see mapping not merely as the act of drawing boundaries or locations, but as a philosophical gesture: a desire to impose logos (reason, order) onto the chaos of space. Maps are epistemological tools — they reflect what a society knows, values, and seeks to control or understand. Maps are also ontological artifacts: they shape how reality is conceived. The earliest Greek world maps, like that of Anaximander, were philosophical propositions as much as geographical representations: they offered a way of visualizing the cosmos and humanity’s place within it. This reinforces the notion that ancient maps were not only geographical but cosmological, reflecting metaphysical worldviews.

Today, as we navigate digital maps, satellite imagery, and GIS systems, we continue this ancient philosophical lineage. Each map, like those of Eratosthenes or Anaximander, is both a reflection and a construction of a worldview—always partial, always powerful. No map is ever a perfect reflection of reality; maps are always created in particular contexts, they are designed to serve specific interests and to communicate certain messages. They are, in other words, arguments about the world, not just representations of it.

Suggested Reading#

📖 “A History of the World in Twelve Maps” by Jerry Brotton